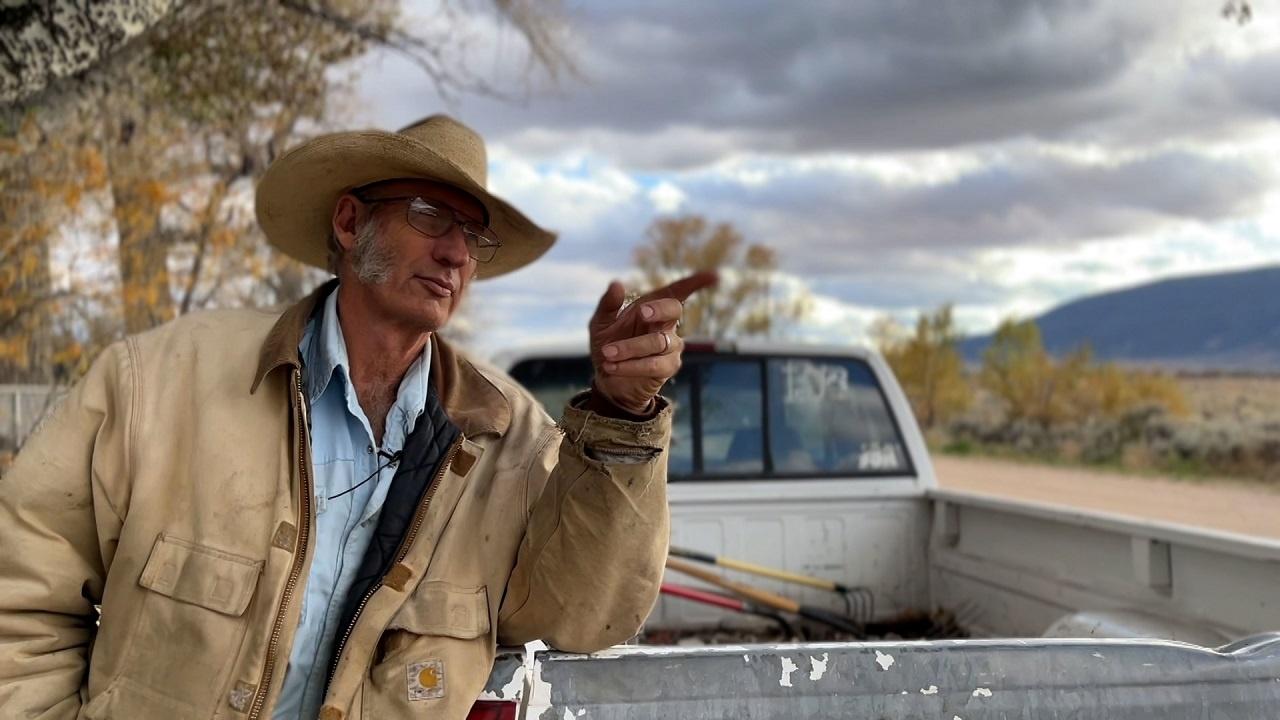

Today, around 40 people remain in the Jaroso area, with a few descendants of the original Seventh Day Adventist farmers and ranchers who came to farmlands sold by the Costilla Estate. Anderson and his son, a fourth generation Jaroso farmer and rancher, are adept at configuring their own engineering of mechanics and equipment. Sprinkler systems, robust wells, and efficiency measures have mostly replaced large-scale flood methods, with a few large landholders still in operation. “Man thinks he's powerful enough to stop it,” Anderson intoned about the fluctuating water supply. “I don't think so.”

The main drag of Jaroso feels more like a driveway than a main street, and it’s a little hard to picture the blossoming town just 100 years ago. Jaroso is no longer a stop on the San Luis Southern railroad. It no longer has a bank, or any of the glossy amenities of a railroad town. The grain elevator no longer brings in barley for Coors. But it has since attracted many artists and people who have become inspired by the attitude of self-sufficiency, innovation, and creativity embodied by the Anderson family today. Anderson himself proudly displays the work of local artists in his home and in the office behind the post office.

After their store closed, Anderson found ledgers tallying credit to local families. Although the Andersons forgave the credit when the store shut down, distant family members of former residents have been known to surface to try to pay back their bills, Anderson said. He always waves them away, knowing his father and grandfather would have done the same. “I don’t know what to say,” Anderson said. “It’s just something you do.”

“As the grandson of my grandfather, and the son of my father — I can’t live with anything better than this,” Anderson acknowledged, motioning over his Jaroso kitchen table with a tear in his eye. “And there's a whole lot of other people in this area that have that same legacy.”

Kate Perdoni is a Senior Regional Producer with Rocky Mountain PBS and can be reached at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org.